The Case for Grass-Roots Ideology

Politics is all too often seen as a dirty game, an exclusive sport with privileged winners and disappointed, disenfranchised losers. If we think of formal politics we imagine the accumulation of power and influence, the control of society. That certainly happens, but politicians don’t get their way without networking, convincing, demonstrating and deterring. Even in societies that lack democracy there is still a great deal of these things going on. I’ve written about this before, labelling it populist governance here in Hong Kong – the pseudo participatory politics that happens when choices are limited. Not much changes, but formal politics is often more about activity than substance.

Politics is all too often seen as a dirty game, an exclusive sport with privileged winners and disappointed, disenfranchised losers. If we think of formal politics we imagine the accumulation of power and influence, the control of society. That certainly happens, but politicians don’t get their way without networking, convincing, demonstrating and deterring. Even in societies that lack democracy there is still a great deal of these things going on. I’ve written about this before, labelling it populist governance here in Hong Kong – the pseudo participatory politics that happens when choices are limited. Not much changes, but formal politics is often more about activity than substance.

And then there are the reactions to situations in which not much is happening – grass-roots politics most people call it. For some, working at the social rather than institutional level is what really matters. Forming alliances where and when you can to support a cause seems pragmatic – we don’t all need to be career politicians. But even then the very notion that attention might focus on just the wrong aspect of an event is frowned upon.

Someone is always ready to claim that someone else is ‘twisting’ a situation for their own gain.

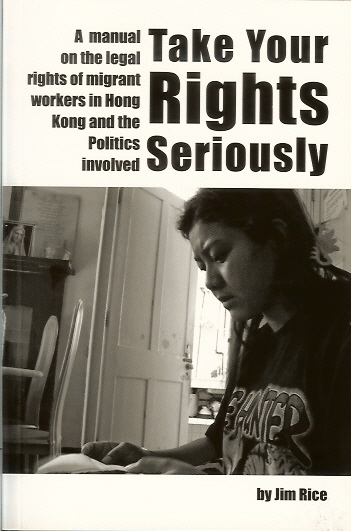

Recently, an accusation of playing politics was levelled against some of the people concerned with the wider implications of the mysterious disappearance and death of Vicky Flores here in Hong Kong. When I mentioned this to James Rice, a fellow member of the Justice for Vicky concern group, a former lawyer and currently an Assistant Professor in philosophy, he said quite enthusiastically, “guilty as charged!”

Recently, an accusation of playing politics was levelled against some of the people concerned with the wider implications of the mysterious disappearance and death of Vicky Flores here in Hong Kong. When I mentioned this to James Rice, a fellow member of the Justice for Vicky concern group, a former lawyer and currently an Assistant Professor in philosophy, he said quite enthusiastically, “guilty as charged!”

What does it mean when we play politics – who really stands to gain? Many times corruption and the naked abuse of power answer that question with ease. But returning to the grass roots, down closer to the dirt of life, there really isn’t much to gain personally from entering the game. It takes up a great deal of time, effort, energy and often money for little reward. In steering a limited issue toward a broader focus, by showing that one event has a context people should care about, the grass-roots player is necessarily ideological, but rarely partisan.

Now this isn’t the most obvious way to describe what happens in politics at the community level. Harry Boyte takes a more conventional approach, arguing that what he calls “everyday politics” involves “civic experiments” and “is more concerned with solving problems than in apportioning blame along partisan lines”. But as I’ve argued before, ideology – as a framework for thought – is intensely personal, and adaptable to new circumstances, new challenges.

Ideology is what makes chance connections in an ad hoc network mean something. It compels people to share a vision of things as they should be, to move into new areas and say ‘something is wrong here too’. If we align ideology with formal politics alone we ignore the many possibilities it opens up.

And, for that matter, there is no compelling reason for grass-roots politics to be part of a civic process, to be civil. To do that the players would have to conform to civic values and at some level support the status quo. At what price do we purchase change if we already subscribe to a belief in inertia?

So when we’re a little ideological in our concerns everyone can stand to benefit, not just those who are the lifeblood of the body politic. The question should never be ‘why are you playing politics?’ That way lies dysfunction. Rather, ask this when you see something wrong in your community: ‘how can we afford to stay the same?’

So when we’re a little ideological in our concerns everyone can stand to benefit, not just those who are the lifeblood of the body politic. The question should never be ‘why are you playing politics?’ That way lies dysfunction. Rather, ask this when you see something wrong in your community: ‘how can we afford to stay the same?’