On Myopic Perceptions of Poverty

Despite a presence so devastating that it makes war seem trivial, poverty is often ignored in our supposedly connected world. Global Issues estimates that half of the world’s population, or around 3 billion people, live in dire poverty. In other words, half of humanity can barely survive. But how often do you think about that? Probably not much if you live in a developed country. Daniel Little recently wrote about the middle class ignorance of poverty in America, something I often observed when living in Australia. It seems like a case of narrow experience over-riding a wider understanding of the world and how it works.

Despite a presence so devastating that it makes war seem trivial, poverty is often ignored in our supposedly connected world. Global Issues estimates that half of the world’s population, or around 3 billion people, live in dire poverty. In other words, half of humanity can barely survive. But how often do you think about that? Probably not much if you live in a developed country. Daniel Little recently wrote about the middle class ignorance of poverty in America, something I often observed when living in Australia. It seems like a case of narrow experience over-riding a wider understanding of the world and how it works.

Little offers an important set of questions that we should be asking, all designed to tease out what we really know about poverty. He also asks how people who are not poor can gain experience of poverty, and suggests that portrayals in poetry and fiction are important in providing a sense of what less fortunate people might be thinking and feeling. But, ultimately, a “cognitive version of myopia” prevents many people from extrapolating that vicarious experience into their own social circumstances, stops them from seeing what is happening around them.

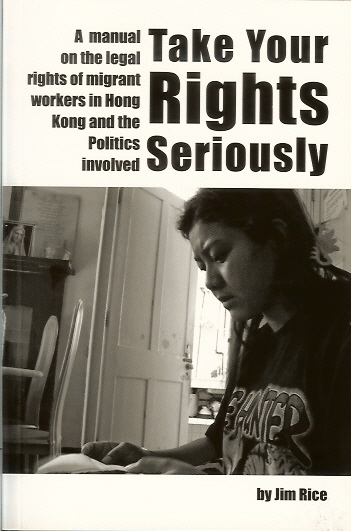

This problem has been worrying me lately as I’ve worked with and talked to Filipino migrant workers in Hong Kong, seeking justice for Vicenta Flores’ family following her disappearance and death. There is often a somewhat narrow perception amongst those with more money and better lifestyles that because a domestic helper earns more money in Hong Kong than she could in the Philippines, she should be happy because she is no longer in poverty.

That might sound reasonable, but it leaves aside any confounding factors such as how many people a small Hong Kong dollar wage can support in the Philippines – or Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand or Nepal for that matter. It also ignores how much money is owed to an employment agency for illegally gathered placement fees and the sheer amount of hours per day that the woman is expected to work. And how do these critics, so ready to pronounce happiness, bother to define poverty?

That might sound reasonable, but it leaves aside any confounding factors such as how many people a small Hong Kong dollar wage can support in the Philippines – or Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand or Nepal for that matter. It also ignores how much money is owed to an employment agency for illegally gathered placement fees and the sheer amount of hours per day that the woman is expected to work. And how do these critics, so ready to pronounce happiness, bother to define poverty?

As Daniel Little makes clear, poverty is little understood. Does an increase in income necessarily relieve someone of the inability to meet their family’s most basic needs in food, clothing, shelter, health or education? Or are there other structural factors in a society that keep some people very poor?

Let’s consider labour imports again. If a woman of any nationality comes to Hong Kong and works as a domestic helper, will the minimum (and usually paid) rate of HK$3480 or US$446 per month actually lift her family out of poverty? She would have around US$16 per day, given an average of 2 days off per month because most employers impose draconian curfews that halve the legally allowed 24 hours off per week. That seems to be well above the often quoted figures of US$1.08 per day for absolute poverty and U$2.15 for nations with slightly higher income levels.

But you have to remember that those figures relate to levels of sustenance just barely above starvation. At US$1.08 per day in even the poorest country, a person could barely survive. And, for the average domestic helper in Hong Kong, the commonly expected and always illegal 18 hour day will yield an hourly rate of only 88 US cents. That still sounds good, but to relate it back to the Philippines – a very poor country by any measure – it would equate to 32 pesos per hour.

So working a 117 hour week a Filipina domestic helper could only send home, at the very most, 16,128 pesos. Given that she would need 5000 to 6000 pesos for her own necessities in Hong Kong, where life for even the poorest is more expensive than in the Philippines, she would be able to feed a family and get kids rarely seen to school. But – and this is important – she could do little else. A single woman or one with fewer dependants would fare better, but income at that level would not extract many people from poverty in most countries. And even half the weekly hours I’ve quoted would break most people – women or men – fairly quickly.

So working a 117 hour week a Filipina domestic helper could only send home, at the very most, 16,128 pesos. Given that she would need 5000 to 6000 pesos for her own necessities in Hong Kong, where life for even the poorest is more expensive than in the Philippines, she would be able to feed a family and get kids rarely seen to school. But – and this is important – she could do little else. A single woman or one with fewer dependants would fare better, but income at that level would not extract many people from poverty in most countries. And even half the weekly hours I’ve quoted would break most people – women or men – fairly quickly.

Happiness with a low wage must be a relative concept.

That domestic helpers can find work in Hong Kong is a blessing, because something is always better than nothing. And not all employers are as unforgiving as I’ve suggested. But to presume that a low minimum wage is sufficient to defeat poverty in a majority of cases is simply wishful thinking.

As Arsenio Balisacan recently argued in the case of the Philippines, poverty can only be reduced when the government commits to more “inclusive” economic growth, focusing on domestic job creation and increased productivity to improve the country’s standing in the global market.

As Arsenio Balisacan recently argued in the case of the Philippines, poverty can only be reduced when the government commits to more “inclusive” economic growth, focusing on domestic job creation and increased productivity to improve the country’s standing in the global market.

In other words, myopic feel-good attitudes about wage levels will change nothing. Poverty will only decline when poor countries no longer want or need to send women abroad, where they are expected to be happy, shut up and keep working.